The Stories of the Gold Rush Children Surviving

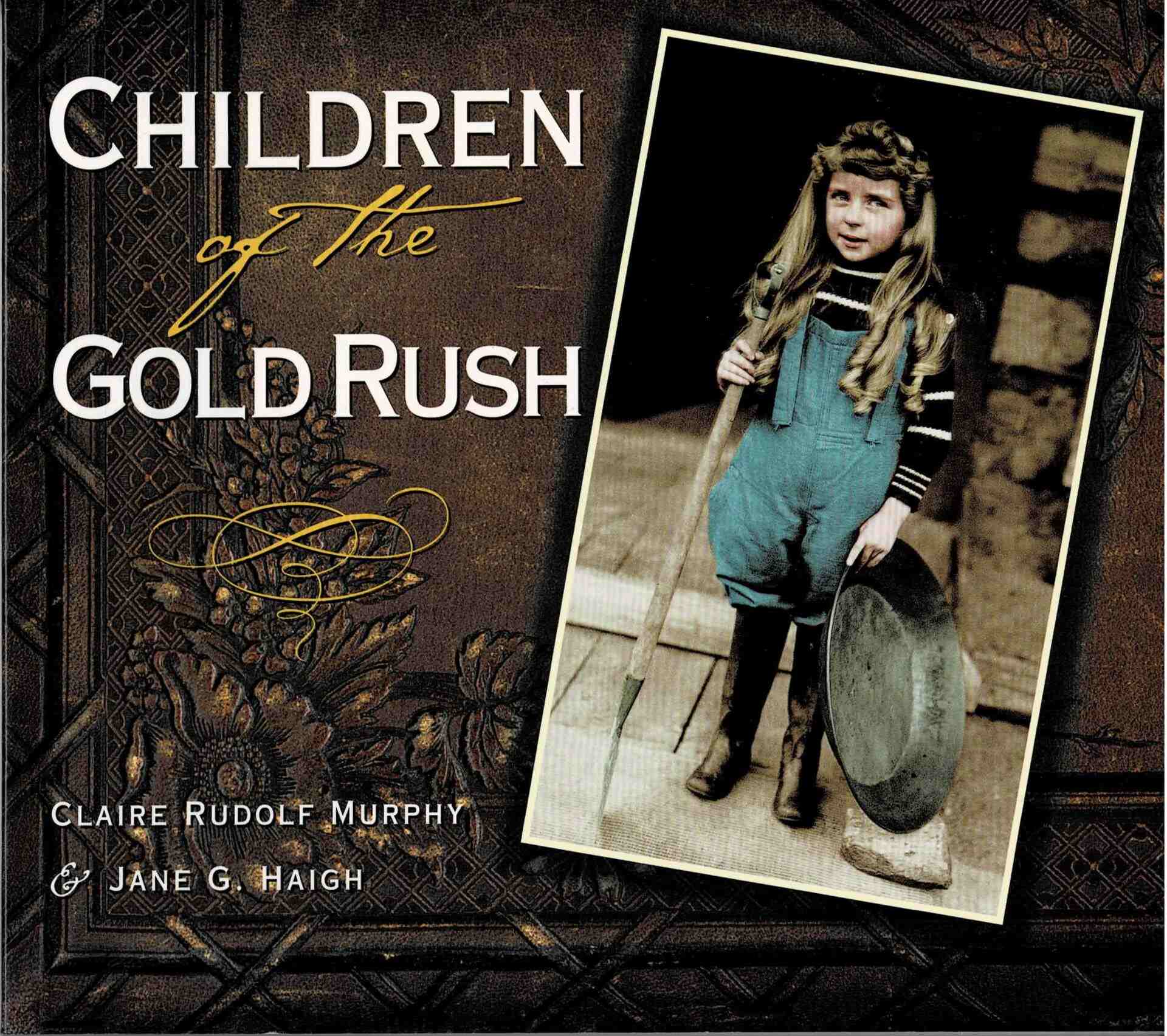

While reading about the women, Jane and Claire were also fascinated by the stories of the many Children of the Gold Rush and decided to write another book (originally published by Roberts Rinehart, then Alaska Northwest Books, 2001).

In vintage photos, personal stories, and related historical material, Children of the Gold Rush portrays the lives of the indomitable kids who first came to Alaska and the Yukon Territory. In a land where freezing, dark winters and mosquito-filled summers challenged even the hardiest pioneers, the children had to be as tough as the adults and quick to adapt to new conditions — learning to eat caribou and moose and dressing in fur. Some children left after a few years; others stayed and raised their own children on the frontier.

Available May 31st, 2022.

Awards

Willa Cather Award

American Booksellers Pick of the List

American Library Association Notable Book Nomination

Reviews for Children of the Gold Rush

Q & A With Claire

Jane Haigh and I had already written a book called Gold Rush Women about all the remarkable women who were involved in the northern gold rushes. When we researched that book, we found kids who had lived up there during that exciting period. We wanted to write about how the children found gold, went to school, played, and sometimes worked as hard as their parents.

When we finished writing about the children, we realized that dogs were important, too. So Gold Rush Dogs came into being. Dogs were more popular than any other animal because they protected the gold rushers from thieves, were loyal companions, pulled freight, and even kept humans warm during the cold winters. That was a fun book to write.

Boy, that’s a hard one. It depends on what my father was like. Some of them were gone for months, even years, at a time and didn’t care much about their families. If he was a good father, I would have wanted to go. But most of them weren’t very devoted to their family, so I probably would have stayed with my mother and helped earn money to feed the family. Maybe I would have sung for the gold miners or panned for gold during recess at my one-room schoolhouse.

Definitely, by boat up through the North Pacific was the easiest way to go. The other routes, you had to hike for weeks over steep mountain passes and then build a raft to float down the Yukon River. All sorts of things could go wrong. People wanting to get to the Nome gold rush from Seattle could take an ocean-going vessel all the way.

Somebody excellent in the outdoors like my husband Bob or brother Matt, and someone who wouldn’t get wild and spend all the gold we found. Many gold miners didn’t hold onto their riches very long. They spent it all in boomtowns like Dawson, Skagway, Fairbanks, or Nome.

This is a tough question. I came to love them all so much. I would have to say I admire the native Athabascan children in a special way because their traditional lives changed forever when the gold rushers came, mostly for the worse. Athabascans Helen and Axinia Cherosky had to suffer through their parents’ divorce, an alcoholic stepfather, and prejudice in Fairbanks, where they went to school. But they grew up to become wonderful citizens of Alaska. I admire Crystal Snow because as an adult she becomes a leader in Alaska, only the second woman to serve in the Alaskan legislature and the first postmistress of Juneau. I hope to write a novel soon based on her gold rush adventures.

Jane and I read all the books we could find about the gold rush, talked to descendants of the gold rushers, and read diaries and articles that the children wrote when they grew up. It was wonderful to uncover their stories and bring them to readers like you.